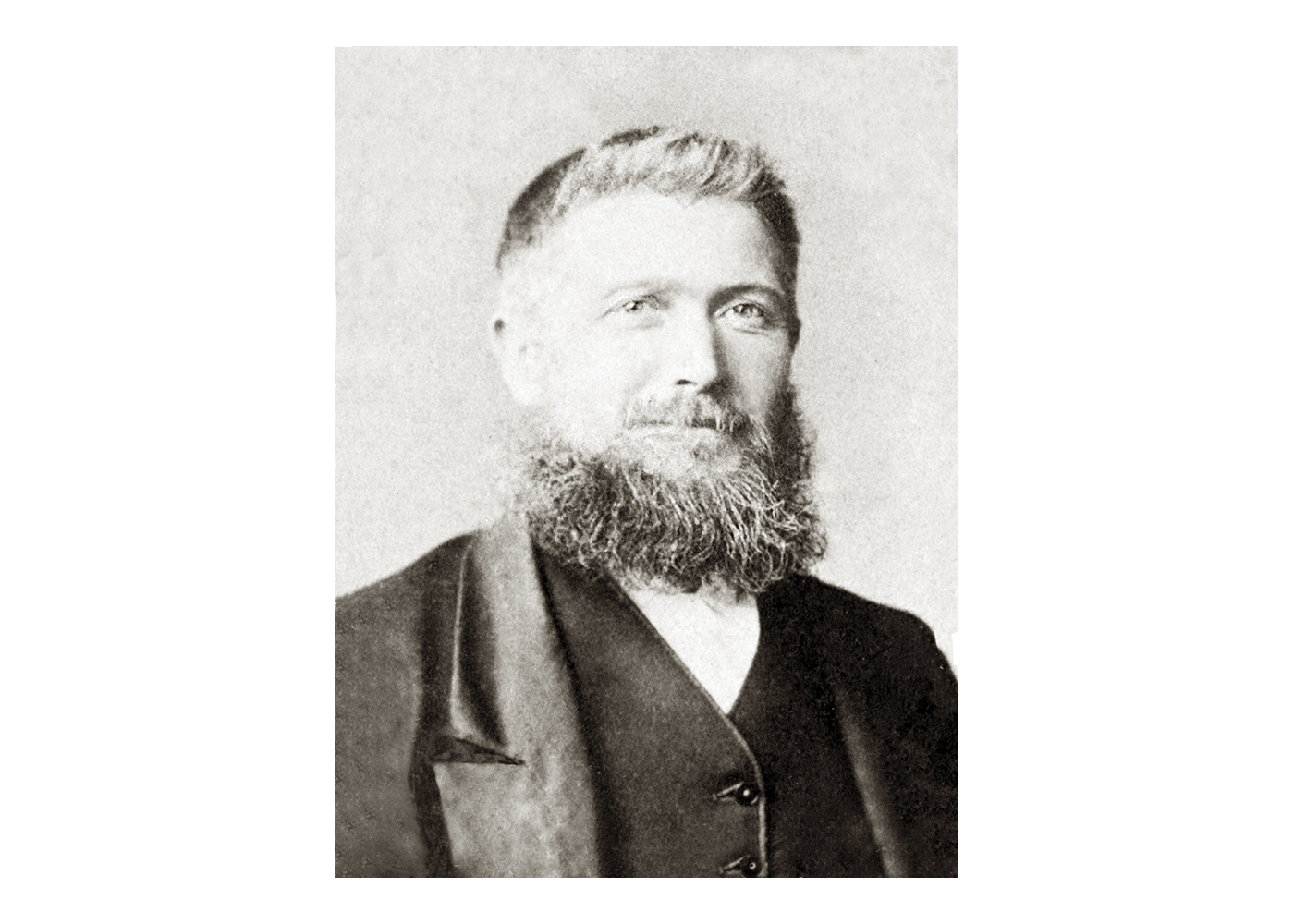

DICK NUNN

Henry Nunn—known to everyone simply as Dick—was, by all accounts, a bit of a lad. He was born in 1836 on Coggeshall’s Rotten Row. When Dick was just two years old, his mother died, but even in childhood he showed a stubborn resilience and a quiet confidence that would serve him well.

Blacksmithing was the family trade, passed down through the generations, and from an early age it was clear that Dick would follow the same path. Apprenticed to his father, he learned the rhythms of the forge and the weight of responsibility that came with it. But fate intervened before his training was complete. His father died of tuberculosis—then a common and deadly illness—leaving the family suddenly without its anchor.

At just eighteen, Dick stepped out of apprenticeship and into manhood. With his family depending on him, he took up the hammer in earnest, determined to keep the forge burning and the Nunn name alive.

As Dick grew older, he became a man of strong opinions and stronger convictions—a born campaigner with an unshakable belief in fairness and a fierce loyalty to the working people of Coggeshall. By then, the town was in visible decline. Cottages stood empty and crumbling, left to rot by their owners, their neglect dragging the whole place down with them. To Dick, this was more than carelessness; it was an insult to the town and to the people who lived there.

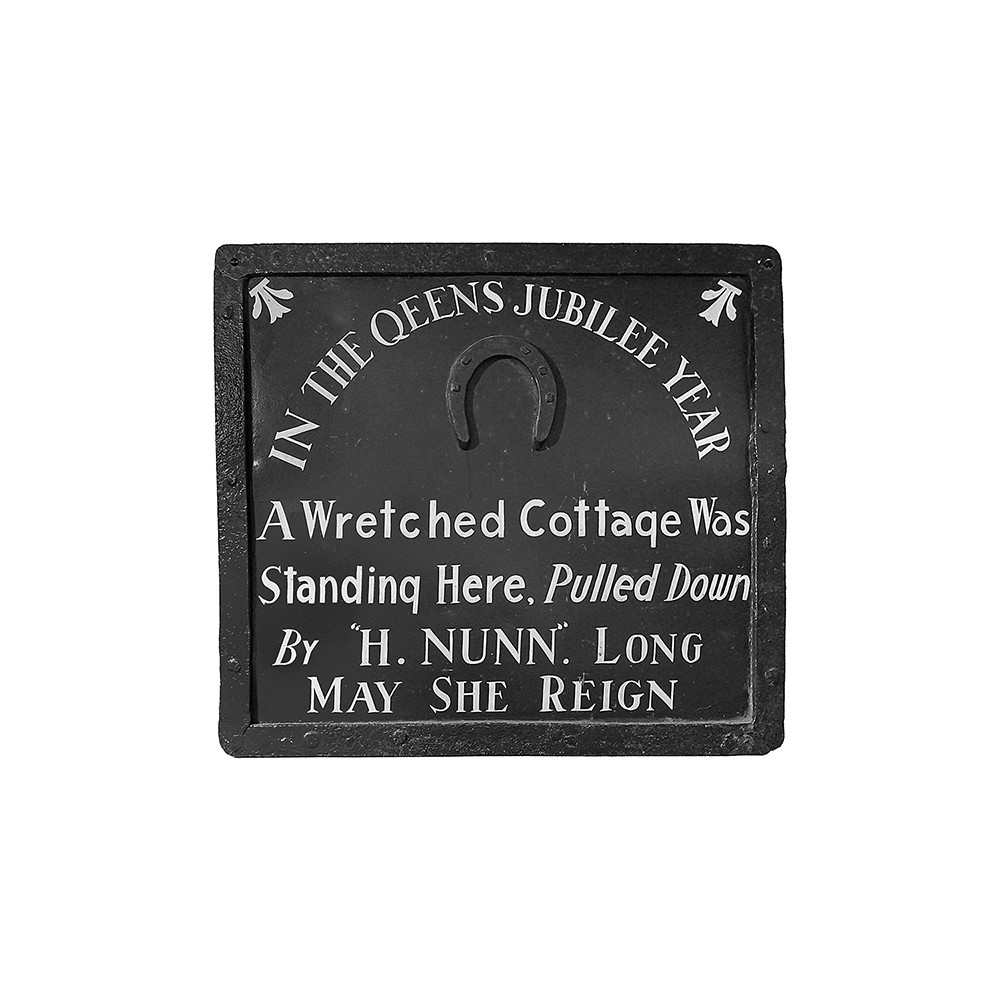

One building in particular drew his ire. In 1887, a derelict cottage standing at the very gate of the church caught his attention. He publicly condemned it as “an eyesore and a disgrace to the beautiful and sacred edifice” beside it—and then, characteristically, decided words were not enough. Dick took matters into his own hands and began tearing it down.

Even an official warning from a solicitor acting for the Lord of the Manor failed to stop him. The work continued, brick by brick, until Dick found himself summoned to Witham Court. But the showdown never came; the case was quietly withdrawn.

Dick treated it as a victory. To mark the moment, he fixed an iron sign to the neighbouring cottage, a defiant memorial that survives to this day. It would not be his last act of rebellion.

He celebrated in his own way, fixing an iron sign to the neighbouring cottage—a defiantly permanent reminder of what he considered a public service. It would not be his last encounter with authority. On Queen Street, another demolition ended with Dick and his helpers being arrested, handcuffed, and left to contemplate their life choices overnight in a police cell. They were released without charge the next day.

On Grange Hill, matters went a step further. While dismantling yet another cottage, Dick was hauled down from the thatch and dispatched to Chelmsford Gaol, where he stayed until a friend paid his bail. He was bound over to keep the peace—a promise that sat somewhat uneasily with a man whose idea of civic duty involved a crowbar.

By the end of his campaign, Dick had demolished eight cottages in total, each condemned by him as “unfit to remain in existence.” It would have been nine but the owner of one on Grange Hill decided to demolish it himself before Dick had his chance. In his own mind—and in the quietly improved streets of Coggeshall—he had left the town a little fairer, even if the authorities were never quite sure what to do with him.

In Dick’s smithy, horses were always treated with care and patience. He understood them, respected their strength, and had little tolerance for cruelty. That was why the sight of horses straining under heavy loads up Coggeshall’s steep Grange Hill angered him so deeply. Day after day he watched animals whipped and pushed beyond their limits, simply because the road was too steep and no one with authority seemed willing to fix it.

Dick did what he was supposed to do. He wrote to the authorities. He wrote to the newspapers. He argued that flattening the worst and steepest part of the hill would be simple enough—“an easy job,” as he put it. But nothing changed.

So, as he so often did, Dick took matters into his own hands. Gathering four labourers and enlisting a small army of local boys to run pails of water from the river to soften the road’s surface, he set to work with picks and shovels. By the time the authorities finally arrived—this time accompanied by the police—half the roadway had already been cut down.

Dick was ordered to stop, reluctantly accepting their promise that the work would now be completed properly. It was a promise that came to nothing. The road was left unfinished, and the horses of Grange Hill continued to struggle—proof, to Dick at least, that sometimes the only way things changed was when someone simply started digging.

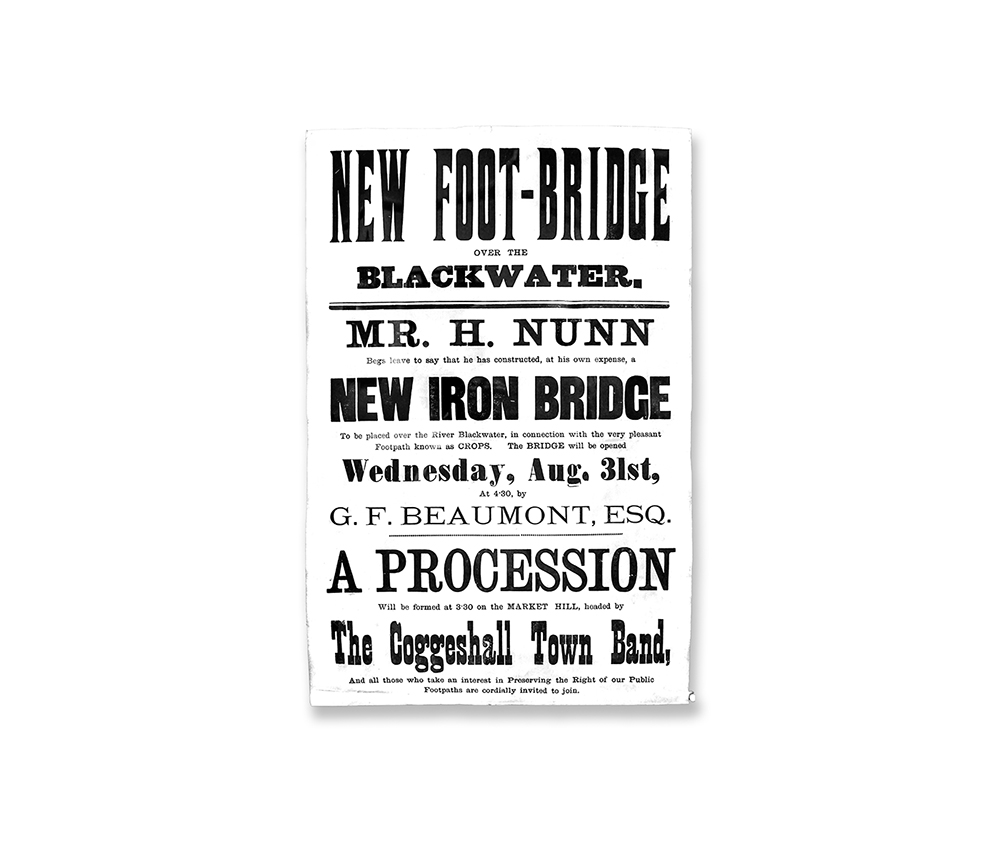

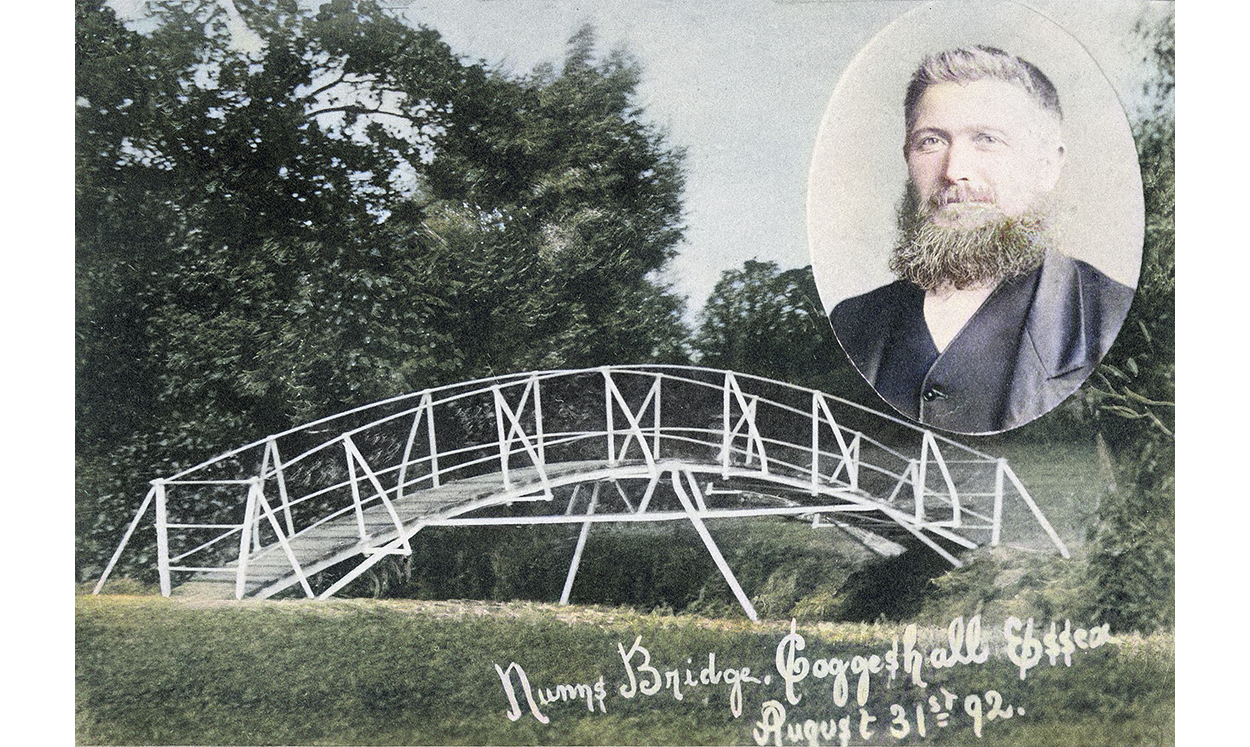

Dick Nunn must have been one of the earliest campaigners for public rights of way. He was determined to keep open the local paths and reopen those that had fallen into disuse. It was his efforts to reopen a path that led him to build the footbridge that to this day is named after him. When the bridge collapsed in 1875 the path was closed and remained so for 17 years.In 1892, Dick took matters into his own hands and set to work in his smithy to built a footbridge himself, using wrought iron which he then painted pink. The completed bridge was mounted on two trolleys and wheeled from his Swan Yard smithy and fixed into position over the river. The grand opening was advertised by a poster which Dick had printed and hundreds of people turned up. With the town band leading, they all made their way in procession to the bridge. Speeches were made and Mr George Beaumont then declared the bridge open and said from henceforth it would be called ‘Nunn’s Bridge’.

The crowd were invited to cross the bridge and pay a toll to help recompense Dick for the cost. Seven hundred and three people were counted over and a total of £12 15s. 5d. was collected, almost half the cost of the project.

Dick was regarded with great affection and when he died aged 60 in 1896, shops were closed and shuttered and hundreds of townspeople turned out to pay their respects at his funeral, following the town band to the church.

Dick and his bridge were never forgotten and the bridge has been repaired and repainted over the years. In the mid 1950s the bridge was in a desperate condition and seeral letters were sent by the parish council requesting repairs be made. They were but in 1957 the Essex County Council who then had care of the bridge were considering whether to restore or replace it. A letter from the parish council made it clear how much the bridge was special to the people of Coggeshall and should be restored. The District Surveyor responded sympathetically and finally in 1962 after 70 years the bridge was restored.

In 1992 the bridge’s centenary was marked with another procession from Market Hill down to the bridge which was decorated with pink crepe paper and pink balloons and speeches were once more heard in praise of our famous blacksmith.

In 2020 after the some of the timber decking fell into disrepair, Essex Highways, (who are now owners of the bridge by virtue of the public footpath which crosses it) made an inspection and concluded that the bridge was no longer fit for purpose and would be replaced. There was huge support from the Coggeshall community for restoration and there were some unsuccessful attempts to persuade Essex Highways to reconsider. This included a survey from one of the countries’ leading historic bridges experts which concluded that the bridge was basically sound. Then an application was made to Historic England to list the bridge and after a tense period of waiting the bridge was listed Grade II. Essex Highways then dropped plans to replace it and the bridge was subsequently restored and opened for use in October 2021.

An official re-opening ceremony took place in the spring of 2022 on the 130th anniversary of the bridge’s construction and opening. An information board has been put up next to the bridge which tells something of Dick Nunn and the how the bridge came to be made. The bridge was declared officially reopened by two long-term Coggeshall residents, Bruce Northrupp and Josie Martin with a sizeable crowd of enthusiastic locals adding their support. With all the publicity the bridge is busier than ever helped also by the two new oak fingerposts, one on the West Street end of the path and the other on the Essex Way. Both these and the information board were funded locally.

The museum has a display devoted to Dick Nunn which includes the old iron sign and one of the original posters.