WOOL IN COGGESHALL

There would have been sheep in Coggeshall before the abbey was built but it was the arrival of the Cistercian’s in 1147 which transformed the keeping of sheep and turned Coggeshall wool into an item of international trade. This is despite the fact that relatively few sheep were resident in the town – never more than 300 compared to 15,00 for example at Fountains Abbey (See the Discovering Coggeshall 2). The abbey sheep did best on the open higher land – the ‘downs’ and the names of two of these Coggeshall downs are known – Ingory Down and Monk Downs.

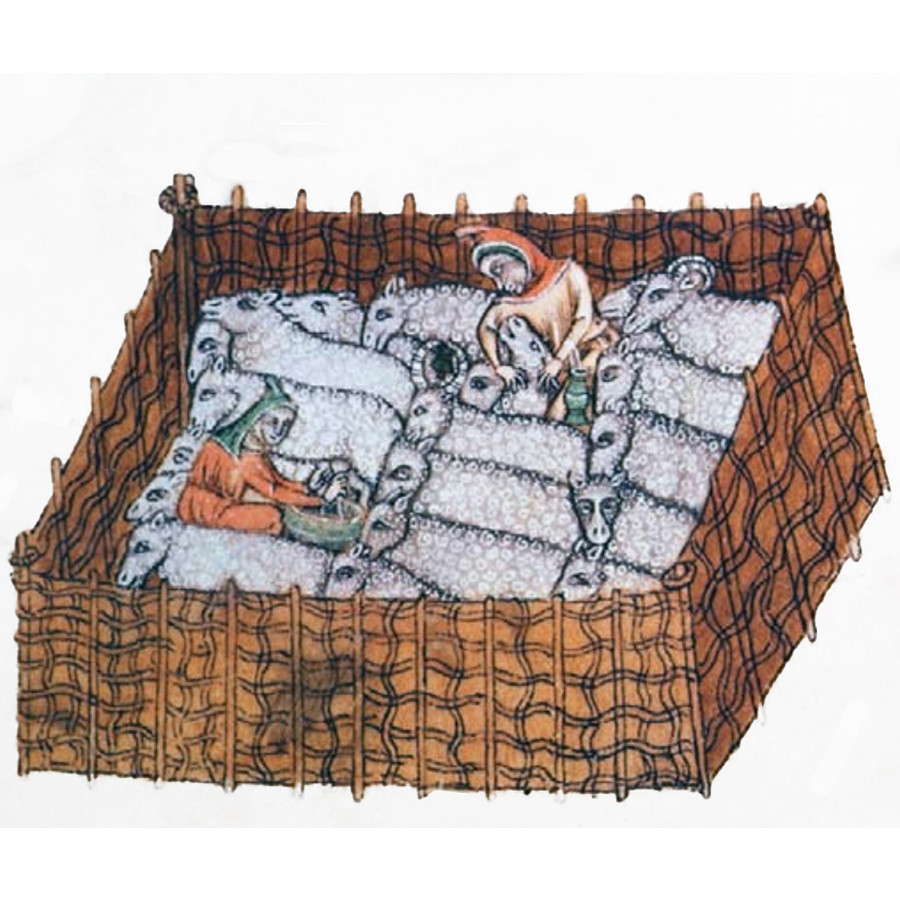

The Cistercians were an agricultural order and grain was the main crop in Coggeshall – evident in the size of the Grange Barn. But the monks did bring expertise into every aspect of the wool trade – enlightened breeding, good husbandry and in its presentation – the cleaning, sorting and grading of the wool. As a result Cistercian wool was regarded as a superior product, which brought a higher price.

In 1250 the Abbey was granted the right to an eight-day fair, possibly a wool fair and in 1256 the right to hold a weekly market – signs of Coggeshall’s growth and increasing population. The earliest market may well have been in the area around ’The Gravel’, as we know it was subject to flooding so it seems to have moved to the area of Market Hill, where the abbey built a small chapel. This increasing prosperity meant that the centre of the settlement moved from around the church to the market on what is now called Market Hill.

The annual Coggeshall Fair was noted for its trade in wool and as early as 1280 ‘Coggeshall wool’ was being traded in the Low Countries and by 1315 in the markets of Florence – at that time almost all the wool was exported. The abbey grew very prosperous on this trade and had the advantage of being exempt from tolls which significantly reduced the cost of transport.

This early prosperity was largely based on wool – not cloth – but weaving grew increasingly important in Coggeshall where it prospered benefiting from the transport advantages of the River Blackwater (to the port of Maldon), Stane Street and the nearby London Road. By 1290 ‘Cogeshale’ was one of four Essex towns exporting cloth from Ipswich. The developing industry was boosted by the arrival of immigrants from the Netherlands who brought both expertise and technology in the production of cloth. By the 13th century cloth-making, mostly in blue or green was well established and in the 14th century using a cheaper dying process, produced a less expensive cloth in russets – shades of grey and brown. At a trial in the Midlands in the early 14th century a ‘Coggeshall Cloak’ is mentioned suggesting both a type of cloth and a product specific to Coggeshall at that date. This was probably a woollen cloth made more waterproof in the fulling process which thickened and felted the material under the hammers in a mill. Coggeshall may at this time have specialised in Chalon (blanket) making. In 1394/5 Coggeshall was the third largest producer of cloth after Colchester and Braintree and by 1467 Coggeshall was the second largest Essex producer after Colchester.

Right; Washing wool

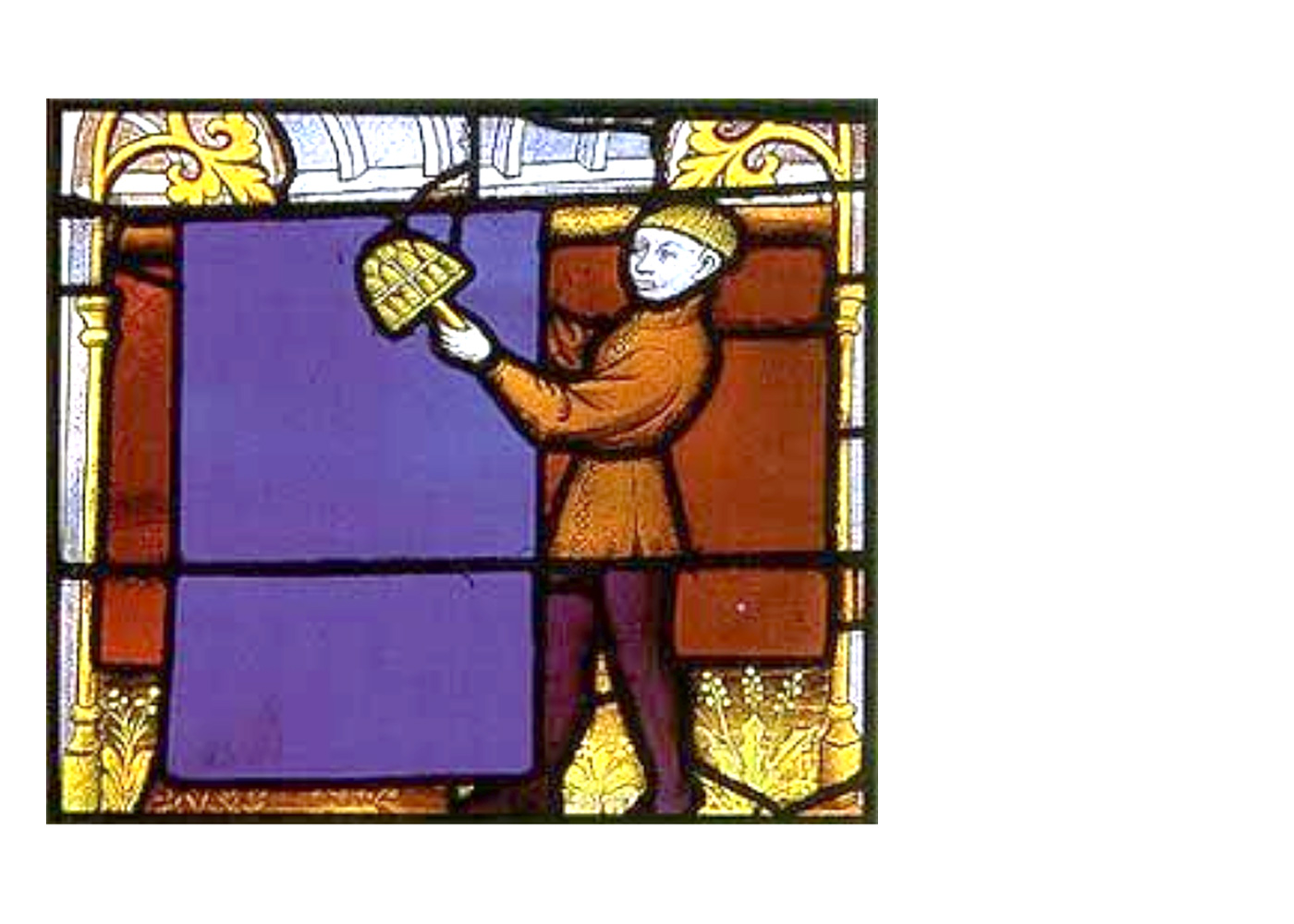

There were many trades involved in the preparation, manufacture and finishing of wool and cloth which included the carding and combing of wool, spinning and weaving, the cleansing and thickening of cloth in the fulling process, dyeing and the growing and preparation of teasels to raise and soften the nap of the cloth. The flowing water of the river, of Robins’ Brook and Pissing Gutter on upper west Street were vital to power the mills or wash and dye the cloth. Fulling was mechanised early on with earliest record of a fulling mill in Coggeshall in 1305.

Left; Using teasels in a frame to raise the nap on cloth

The growth of Coggeshall in the fifteenth century also owed something to the local clothiers who adopted a production system which saw them supply the wool, outsource the preparation, weaving and finishing processes, then using regional markets to sell the cloth to drapers. The Paycockes were just one such family of clothiers, wealthy enough to build a chapel in the church dedicated to St Catherine and an expensive house. Coggeshall had many prosperous and perhaps less ostentatious clothiers and there are many timber framed houses dating from this time.

The worsted industry began with the arrival of continental emigrants. An Italian, known as Bonvise, arrived in Coggeshall in 1539 and started the manufacture of undyed cloth called ‘Coggeshall whites’, for which the town became famous and which was known colloquially as ‘Coxsall’. Contemporaries regarded these lightweight woollens as ‘the best whites in England’. In 1566 Dutch and Walloon immigrants arrived, driven from Holland by religious persecution and settled in this area of Essex. The Coggeshall name is also associated with a superior type of bay made with fine fleece wool – a ‘Minikin’ recorded in 1640.

Lead seals were were attached to textiles from the late 14th century in England as part of a system of industrial regulation and taxation and some of these seals from Coggeshall have survived by chance – seven fragments were recovered from a well in the city of London.

The seal illustrated was found in Colchester by Dave Martin. Dating from 1621 it shows a cockerel in the centre (a pun on the town’s name) and around the edge ‘100 BAYS 16(21) CO(XALL)’ – missing parts in brackets. The seal is 45mm in diameter.

Celia Fiennes wrote in 1698; ‘great quantetyes are made here and sent in Bales to London: the whole town is employ’d in spinning, weaveing, washing, drying and dressing their Bayes, in which they seem very industrious’ and ‘the low grounds all about the town are used for whitening their Bayes for which the town is remarkable’. (this was written of Colchester but would have been much the same in Coggeshall)

The cloth was stretched out to dry in the sun on great frames using hooks called tenterhooks to hold it taut. The practice is recalled in Coggeshall in the name ‘Tenter Field’ near Grange Hill and to the west of Stoneham Street. The word ‘tent’ and the expression ‘on tenterhooks’, derives from this process. By the close of the 16th century Coggeshall was second only to Colchester as the largest producer of cloth in Essex. The parish church had been completely rebuilt in about 1420 and then again in 1570 – 1650, to become the third largest in Essex (after Saffron Walden and Thaxted) and like them, built from the profits of wool and weaving.

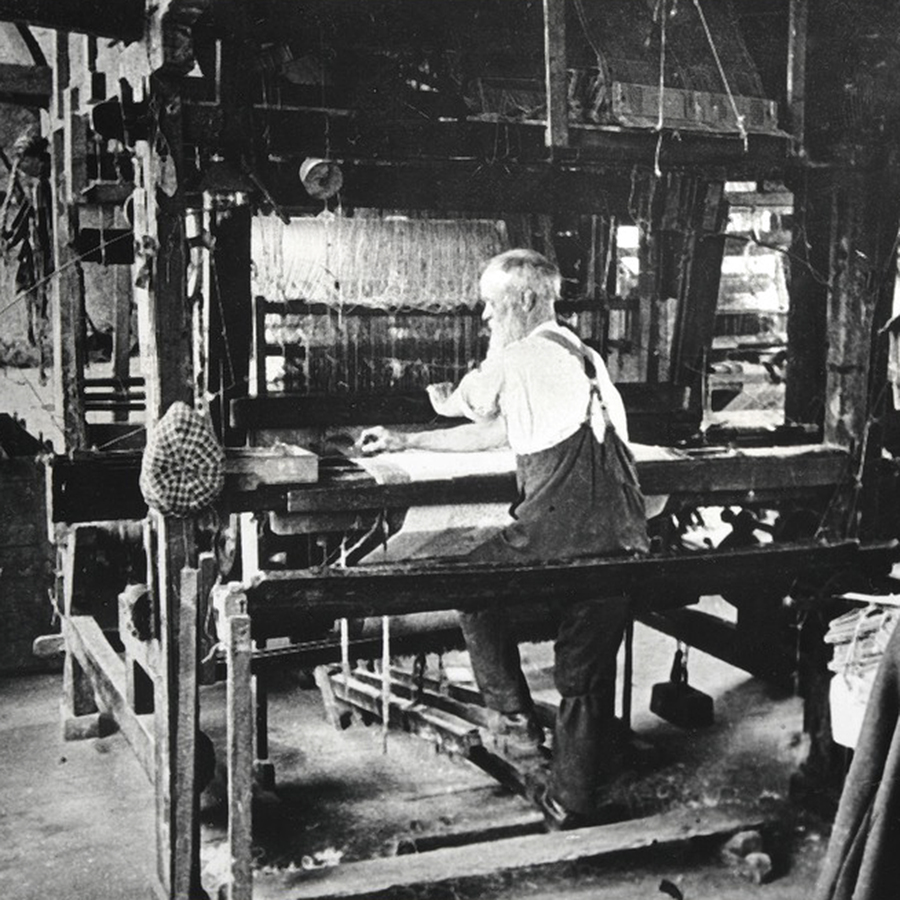

In 1733 one of weaving’s greatest inventions, the flying shuttle, was first used and developed by John Kay in Coggeshall where he operated a number of looms, but by the end of the 18th century weaving was in steep decline. The trade had moved mainly to the north of England and Kay himself decamped from Colchester back to Lancashire where conditions were more suited to industrialisation. The last woolen mill to be worked in the district was that at Bocking which closed down about 1815.

Many of Coggeshall’s weavers transferred to the newly developing silk industry which boomed as wool declined.

In the museum there is a working wool loom on which demonstrations are given from time to time. It was Coggeshall resident Jack Thornton who restored the loom to working order.

Further Reading: There is an up-to-date account of the wool and cloth trades in ‘Discovering Coggeshall 2’ Ed David Andrews, Pub John Lewis, 2013

Kay’s presence in Coggeshall and Colchester has been disputed.