HENRY DOUBLEDAY

Henry Doubleday was born in 1810, the fourth of eight children. His father William came to Coggeshall in 1789 and opened a grocery shop at Market End. The family played a leading part in Coggeshall’s Quaker community, they were prosperous and in many ways remarkable. Henry’s cousin, also Henry (whose father was also a grocer), was a Victorian butterfly hunter who compiled the first catalogue of the British Lepidoptera and his brother Edward became curator of the Botany Department at the British Museum. Like them Henry had a love of the natural sciences but despite the fact that as a Quaker he was unable to study at university, he developed a scientific and practical knowledge of plants and plant chemistry. Henry was a religious man in the thoughtful and reflective Quaker tradition and talked of ‘observing the works of God in humbleness’ – his scientific investigations were made with a sense of discovery and wonder rather than as a means of personal aggrandisement or fame.

Unsurprisingly perhaps, Henry had no interest in the family grocery business, which his elder brother, William was happy to take on when their father died. Henry never married – Quakers had to marry within their own community which rather limited their options – and he lived his whole life in the rambling old house behind the shop.

Henry worked a smallholding off Robinsbridge Road and rented at least one other piece of land near the abbey mill. He grew crops, raised cattle, kept three cows and a pony and several hives of bees. His smallholdings enjoyed a measure of success and were both a means of earning a living and a laboratory for his experimental crops. He was always investigating and trying out new things.

Much affected by the suffering caused by the Irish famine Henry tried to find a blight-resistant potato and for years searched any blighted fields for resistant plants. This led him to a strain he called ‘Berkshire Kidney’ which he grew for years, only to find that it too was swept away in a year when the blight was particularly rampant. The potato, although it fell at this hurdle, had qualities enough for him to sell his stock to Sutton’s Seeds of Reading.

Henry had two exhibits at the Great Exhibition at Crystal Palace in 1851 which demonstrate his resourcefulness. Firstly he produced a hive of honey, as the Essex Standard put it, ‘contained in a very handsome carved rosewood frame, with plate-glass sides and top, the industrious bees have completely filled it, so it presents now a singular and beautiful appearance’. This may have been one of the first observational bee-hives – something which is now quite familiar to us. His other entry in the Exhibition seems very unlikely – new designs for Tambour lace. Coggeshall lace was important at the time and Henry for some reason must have turned his analytic mind to producing new patterns which were worked in lace and earned him a bronze medal and a statuette of Prince Albert.

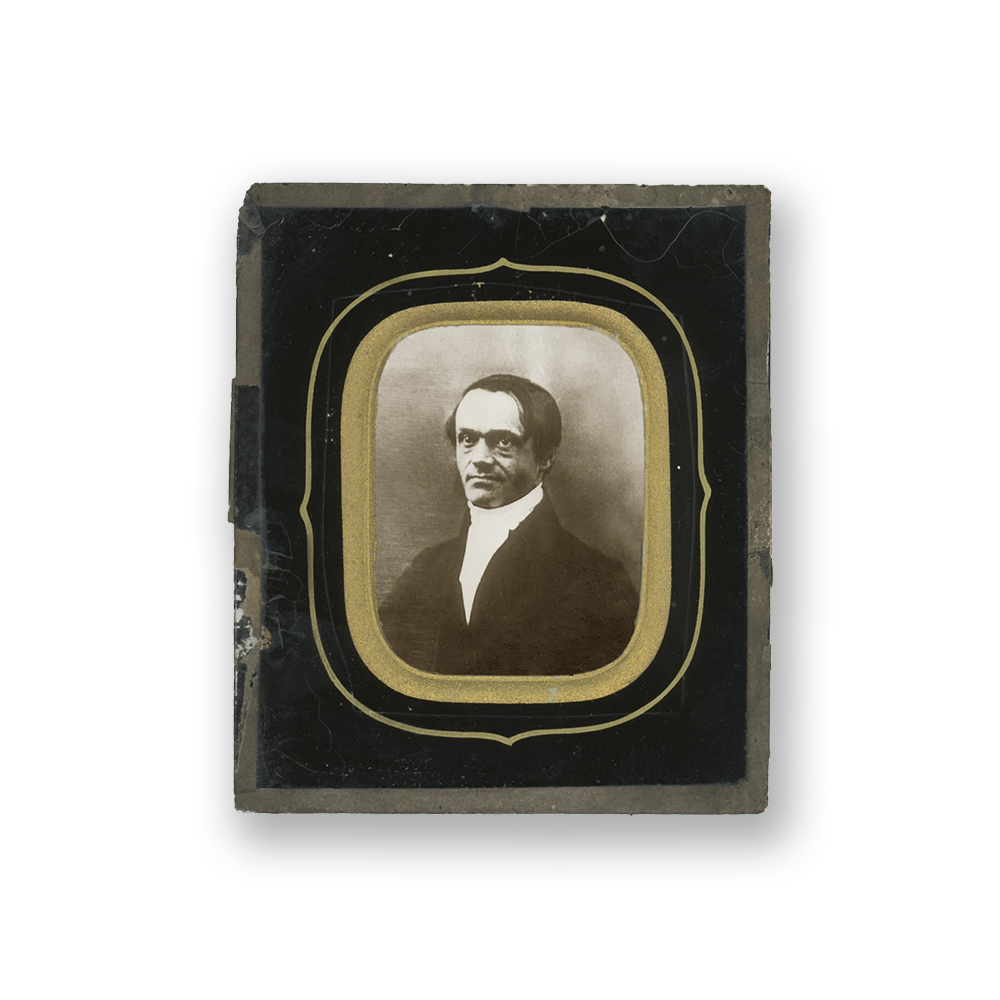

It was whilst visiting the exhibition he had his portrait taken – a daguerreotype. Photography was then quite new and Henry had to sit without moving for 30 minutes – which probably explains the rather stiff pose of someone determined not to blink.

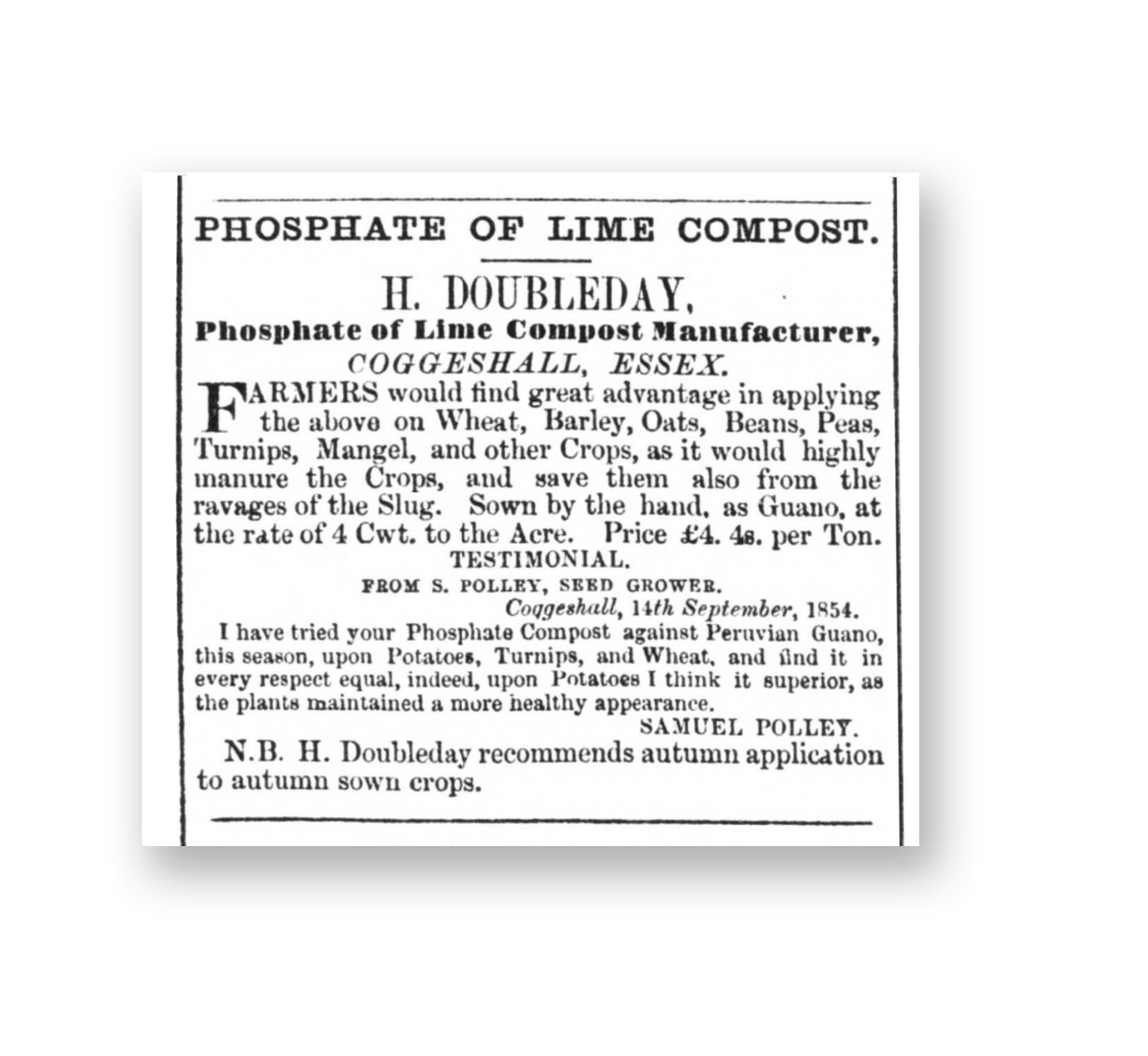

In the 1850s he was a manufacturer of ‘Phosphate of Lime Compost’ and he probably produced and sold seed, not unusual in Coggeshall. In was reported that in 1856 a thief broke into his store – a house at the top of Tilkey Road and stole 60 lb of broccoli seed – far more than Henry could have used himself.

It may have been his work on blighted potatoes that led him to investigate starch. In 1856, he was granted a patent for ‘An improved method of making Starch’ and using this he opened a factory in Coggeshall making and packing starch for sale by grocers to housewives. This business failed, according to Henry’s nephew Thomas, because the factory manager proved dishonest. It must be said that Henry was a very poor businessman – he probably had little interest in it – and spent most of his life in poverty as a result.

Henry also manufactured his own glue – for which he was also granted a patent. To use the first postage stamps the user had to find his own adhesive to attach them to an envelope. A search to find a suitable glue proved fruitless until Henry invented his patent adhesive made from a combination of gum arabic and animal glue. This had the necessary properties of only becoming sticky when wet, yet surviving the damp and humid conditions of the tropics, without having the sheets stick together. This brought him a contract to supply the firm of De La Rue, printers of postage stamps. (the fourpenny carmine was their first stamp)

Unfortunately supplies of gum arabic, derived from an extract of the Acacia tree, were erratic and Henry was forced to look for an alternative source which could be grown in Coggeshall. Reading the journal of the Royal Society of Agriculture he came across a description of a Russian Comfrey to which the word ‘mucilaginus’ (having a viscous or gelatinous consistency) was attached. Thinking that this might answer his requirement he sent off a letter to the Head Gardener, The Palace, St Petersburg. Catherine the Great, had decided that her head gardeners should always be either English or Scottish and this rule had been followed after her death. So the English gardener there sent him back some seedlings – making Henry the first to import them into England. After selling his stock of potatoes to Suttons he replanted his plot near the abbey with this Russian Comfrey. The plants thrived in Coggeshall and produced a prodigious crop but ultimately the gum produced was ineffective and Henry lost the contract with DeLaRue and had to sell the factory.

His interest in Comfrey however, continued. It had been used for centuries for treating wounds, especially in horses but the plant also exhibited a range of other potentially useful qualities – it could cut be cut several times a year to yield over a hundred tons an acre and as a forage crop it was very nutritious and much savoured by animals. Henry thought that this was a crop which might prevent starvation in the world. He experimented with an underground concrete silo to store the crop where it would, like modern silage, turn some of the starch into sugars and then remain without deterioration until it was required.

Henry’s work on Comfrey was recognised and he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Horticultural Society – but never added ‘RHS’ to his name as he was too poor to afford the £12 registration fee.

Henry continued to work on Comfrey for thirty years keeping meticulous records of his work. He gained some income from his plants whose commercial exploitation he entrusted to a friend but of course he never became wealthy from it. Henry’s Comfrey did find its way to the USA where all commercial Comfrey derives from his stock. Comfrey is also the main ingredient of a well known liquid plant food and is still the subject of experiment and debate.

At the end of his life Henry was looked after by his nephew and niece Thomas and Edith who had taken over the Doubleday shop. Henry would walk up to the Quaker burial ground at Tilkey where more and more of his friends lay as he outlived them, ‘A tall thin figure in a long black overcoat, the children would run after him and ask the time, because to their delight, and he would stop and take out a gold repeater watch that chimed the nearest hour’.

In the 1950s a horticulturalist called Lawrence Hills inspired by Henry Doubleday’s work decided to set up his own smallholding in Bocking to investigate Comfrey and encouraged others to share his researches, particularly into ‘companion’ planting for pest control, and in 1958 he created a membership organisation to support the research into comfrey and organic growing. He named it the ‘Henry Doubleday Research Association’.

Lawrence Hills visited Thomas and Edith in the old house behind the shop in the 1950s. The grocers shop itself had closed in the 1930s and leased to an old fashioned gentleman’s outfitters but as Lawrence said ‘not even in the sleepy town of Coggeshall were there enough old fashioned men to keep it going’. Lawrence was hoping to find records of Henry Doubleday’s experiments, but Edith, then 96, slowly told him that it took them two days to clear Henry’s rooms; they had stuffed all his papers into sacks, taken them down to the yard and burned them – everything had gone. Shamefully the shop and the house behind were themselves razed to the ground in 1960 and a concrete monstrosity now stands in its place, leaving the name ‘Doubleday Corner’ as the only reminder of this remarkable family.

Except of course for the charity, the Henry Doubleday Research Association which grew steadily in the 1960s, but really took off in the mid-1970s when ‘growing your own’ surged in popularity. It set up the Heritage Seed Library in 1975 to protect hundreds of vegetable varieties endangered by new EU regulations. HRH The Prince of Wales became Patron in 1988 but the connection with Henry Doubleday was lost when the charity was renamed ‘Garden Organic’. Their Schools Scheme involves 10 per cent of all schools in the UK and their Master Composter and Master Gardener programmes have trained hundreds of volunteers to inspire their communities. Major research projects help growers adopt organic methods and Garden Organic has become the largest organic gardening and horticultural organisation in Europe. Henry, I am sure, would have been astonished.

Henry Doubleday of Coggeshall 1810 – 1902