STRAW PLAITING

Plaiting was a cottage industry carried out by women and children and most of it went to the hat-making industry in and around Luton and Dunstable where men’s and women’s hats and fashionable bonnets were made.

Plaiting, or braiding as it was locally known, was first introduced in Halstead about 1795 by the Marquis and Marchioness of Buckingham, of Gosfield Hall, to provide income for the distressed poor. The Buckinghams hired an instructor from Dunstable to teach local women the art of plaiting and the trade quickly spread to the villages in north Essex where there had previously been wool spinners. The trade boomed during the Napoleonic Wars when supplies of plait from Italy were cut off and duties were imposed on other imported plaits.

The trade was centred on Halstead but was established in Braintree, Bocking and in Coggeshall where by 1807 there were many straw plaiters or braiders at work. Arthur Young wrote in that year that ‘large earnings are made’ in Coggeshall. Braiders here not only sent their work to the dealers but also supplied three Straw Bonnet Manufacturers; Mrs Eliza Surry and Frederick Lawrence both of Church Street and Alfred Wheeler of Market Hill and five Milliner’s (finishers of women’s hats); Miss Susannah Ambrose of East Street, Mrs Ann Antony of Church Street, Miss Christience Davey and Henry Moore both of Market End and Mrs Kezia Norman of Stoneham Street. (The Post Office Directory for Essex Herts and Kent, 1855)

Portrait of Henrietta Liston dated 1800 showing a plaited straw bonnet with silk lining and embellishments.

Straw for plaiting was harvested by hand as machine reaping damaged the stems. The stalks were sorted according to their diameter, a process which was essential to produce an even plait, and cut to length between the joints to create usable straw of 9 – 10 inches / 225 – 250mm long. Although this preparation work was at first carried out by the plaiters themselves, the emergence of a middle-man called a ‘Factor’ saw the trade develop. Factors conveyed the plait to specialised markets like that at Hitchen and would also supply straw, sometimes specially grown, already split and ready to work into plait. This plaiting straw trade came in 6 inch/150mm diameter bundles.

Producing Plaiting Straw

The illustration shows the straw being sorted by the diameter of the stem – each box has a grid of different sized holes. The chap sitting down is gathering the sorted stems and tying and trimming the bundles (which can be seen at his side) ready for sale.

At the start of the plaiting process, the straw was split into a number of strands or splints, a process simplified when a straw-splitting ‘engine’ was invented in London in around 1798 (This splitter was probably not invented by French prisoners of war as is often claimed). It was the splitting of the straw which made it possible to plait fancy straw patterns and this changed the plait from a rough and ready rustic material into the fine quality product favoured by the fashion industry.

By 1800 splitters were being used in Essex usually splitting the straw into seven splints as the seven-end whole straw plait became the staple of the hat industry and the first plait to be taught to children. For the very finest work the straw was divided into anything up to twenty splints.

One of these splitters (shown here) can be seen on display in the museum and is an early example made from bone, later splitters were made from metal.

After splitting the splints were steeped in water (sometimes with brimstone – what we now called sulphur added) to make them more pliable and then softened using a rolling pin or a more expensive splint mill where hardwood rollers squeezed the splints. The plaiters, almost always women and children, held a bundle of splints under the left arm, and each splint was drawn out and moistened between the lips before being worked into the plait. The work continued with new straws added to the weave and overlapped to trap them, until some twenty yards were produced, called a ‘score’ – the yard traditionally measured from the nose to the fingertip of an extended arm. The protruding part of the overlapping straws were trimmed with scissors or shears and the plait rolled until flattened.

Splint Mill photo courtesy Veronica Main (see below)

Straw plaiting brought a degree of independence for women; at times they could earn considerably more than the men. Plaiting did not require them to be at home or even to sit down and could be done whilst child-minding and in company. In the early days women could earn three to four times the income they had made from spinning and considerably more than an agricultural labourer. Predictably this brought complaints from men in authority who found the women less compliant than before, ‘it makes the poor saucy, and no servants can be procured, or any field-work done, where the manufacture established itself’ (Arthur Young, ‘General View of the Agriculture of the County of Hertfordshire’ 1804).

In the illustration the yet untrimmed overlapping splints can be seen sticking out of the plait.

Plaiting Schools were set up where parents would pay a few pence a week for their children to be taught the craft, alongside more traditional instruction. Children were soon capable of producing good plait and some at least were compelled to work for many hours a day to help supplement a families’ income. Labourers later said that the only knowledge of reading they ever gained was from their attendance at these plaiting schools.

There were many different types of plait with names like Feather Edge, Dunstable Twist, Whipcord, Rustic and Pearl. One of the most attractive was known as “Brilliant”. The shiny faces of single splints were set at an angle to one another, giving a kind of check effect. Brilliant needed considerable skill to make well and probably only those who had learnt it in childhood ever really mastered it. A fine Leghorn plait would normally use 13 splints – generally speaking the more splints used and the more complex the design, the greater the price that could be obtained.

Plait was often bleached – the plait was draped across bars inside a wooden box with an open base which was then placed over the glowing embers of charcoal to which a pinch of sulphur was added. As the trade developed the straw plaiters increasingly left the bleaching and colouring with dyes to the suppliers of straw or to the hat manufacturers.

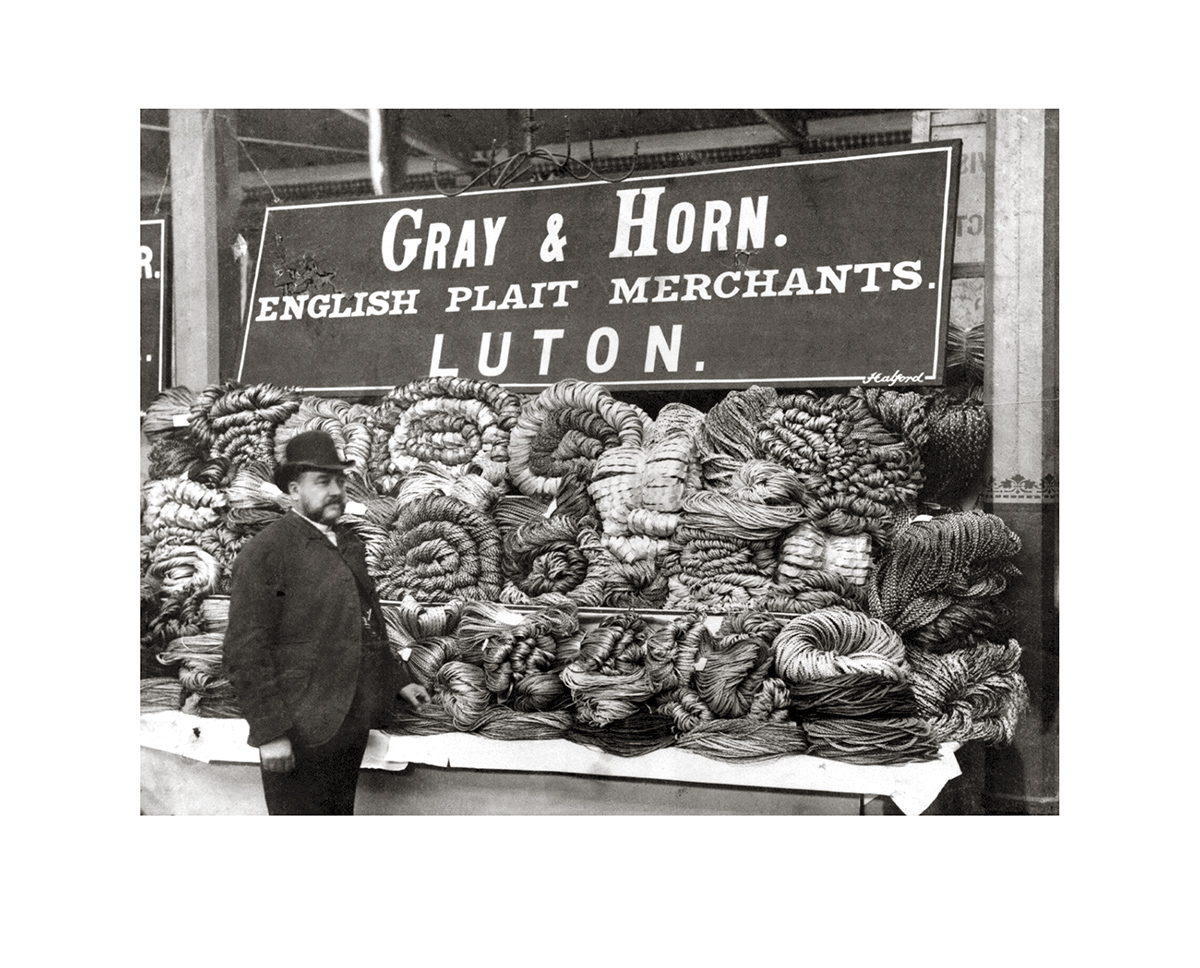

In Coggeshall some plait went to the town’s own hat-makers but most of it was sold to Factors or dealers such as Thomas Linsell or Joseph Cornell from Halstead who in turn sold it in the hat making centre of Luton.

The peace following the battle of Waterloo in 1815 saw prices fall as an imported, higher quality and cheaper Italian ‘leghorn plait’ came to dominate the market (this was made from a variety of grass picked green). In 1818 a family could still make as much or more in a week as a man earned as an agricultural labourer but by 1820 it was said that there was little or no money to be made in the trade. In 1824 a Halstead women asking for poor relief claimed that ‘Braiding is no use for it fetches nothing when tis done worth speaking on’. Straw plaiting as a profitable occupation virtually ceased and in Coggeshall as elsewhere families who had come to rely on it, returned to poverty. Braiding was finally killed off in the 1870s with a flood of cheap imported plaits from Japan and China. In 1882 there was a single Straw bonnet manufacturer, Frederick Lawrence, at work in Church Street Coggeshall and he would have been using imported plait.

To create a hat or bonnet the plaits had to be sewn together in a spiral, starting at the crown and finishing at the brim. This took considerable skill as the stitching needed be invisible and the hat approximately formed to the required shape. A sewing machine was eventually invented capable of doing the job but in towns like Coggeshall supplying a limited local market it is doubtful if such machines were affordable and hand stitching remained the norm. After stitching the hat would be pressed into a moulded former using steam to produce the finished shape.

Coggeshall’s Milliners would finish, decorate and sell the hats and bonnets with linings and ribbons from one of the many silk manufactories in the town. The milliners would have continued in business after the straw plait industry collapsed using imported plait from China and Japan. Kate Chilcot (see photo) with her shop in Church Street may have been the last of the Coggeshall milliners.

Further Reading

The best website for straw plaiting: https://www.hatplait.co.uk

Straw-Plaiting – a lost Essex Industry, I Chalkley-Gould, Essex Naturalist, Vol. 14 p 184 (1905)

The Workwoman’s Guide from 1840 By ‘Workwoman’, AKA Lady Maria Wilson, Simkin Marshall & Co, 1838 (Google Books)

The Hat Industry of Luton and its Buildings, Katie Carmichael, David McOmish and David Grech, English Heritage, 2013

Imports, Mechanisation and the Decline of the English Plaiting Industry: the View from the Hatters’ Gazette, Luton 1873-1900, Catherine Robinson, 2016;

Children of Straw, Laszlo L Grof ,Barracuda Books, 1988

Leeds Mercury 24/12/1860

Temporal blessings Poor women’s employment in Essex during the French wars 1793-1815, Pamela Sharp, Transactions of the Essex Society for Archeology and History 1996, Vol 27, p230

Straw Plaiting: Heritage Techniques for Hats, Trimmings, Bags and Baskets, Victoria Main, Herbert Press/Bloomsbury, 2023

Victoria County History of Essex Vol 2, p375, Archibald Constable, 1907

Trevor Disley

Last update: August 2023