THE TOWN CLOCK

The Origin of the Clock

Anciently a chapel stood in the centre of the Market Hill which was built by Coggeshall Abbey so that visitors to the market had somewhere to offer up their prayers and their cash.

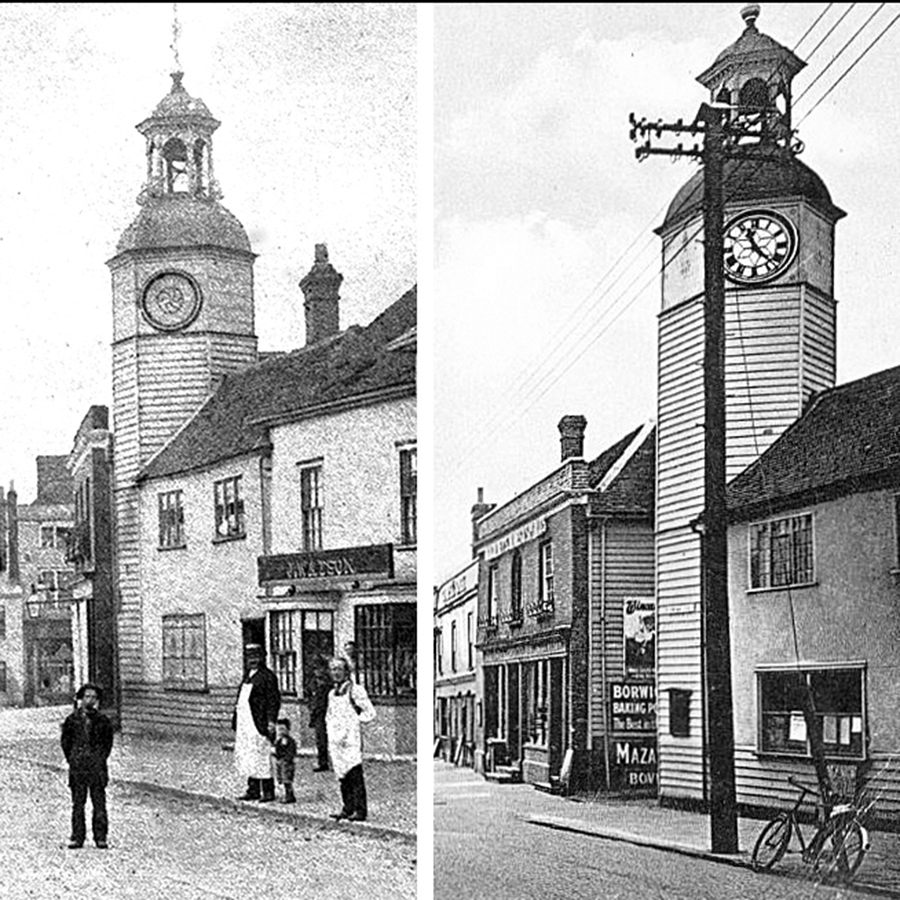

In 1588, after the abbey was dissolved and its holdings dispersed, the chapel’s then owner Robert Wordsworth gave it for the benefit of the poor of Coggeshall. The old chapel at that time was used as a corn and butter market but in 1615 it was rebuilt as a market house and wool hall. It then had an open ground floor where stall holders would have sold their wares, a first floor hall and above the roof a clock in a turret. A clock was thought essential ‘for the better ordering of apprentices’. The building would have looked much like the surviving Market Hall at Thaxted. The diarist Joseph Bufton tells us that in 1686 a new clock was installed, it came from London and cost £23.

Html Light Grey background ignore this text it is just to increase the picture size

ignore this text it is just to increase the picture size

ignore this text it is just to increase the picture size

By 1787 the trustees of the charity who owned the building had allowed it to fall into such a state of disrepair that it had to be pulled down. Some of the money from the sale of its materials was used to relocate the clock to its present position. This was on the corner of a building used as a school room and called the Crane House after its benefactor. The pupils of Sir Robert Hitcham’s Grammar School were based there until 1859.

The old clock from the Market Hall seems to have had a complicated history, one unverified report claims that the ‘weavers’ installed a new clock in about 1800, the bell was certainly renewed in 1843 and the carpenter’s name ‘R Saunders 1875’ is carved inside the cupola recording a restoration event. Whatever it’s history, by the second half of the nineteenth century, the clock itself was becoming notoriously unreliable and more often than not had stopped, showed the wrong time or struck the wrong hour. It had become something of a joke locally and gave rise to one of the notorious ‘Coggeshall Jobs’.

When the town began to think of how to celebrate Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee in 1887, a new clock quickly became the favoured choice. The first plan was for a new clock in a brick tower to be built in the centre of the Market Hill. A design for this had been drawn up by a Coggeshall native, one of the Doubleday family who was an architect in the Midlands. Efforts to raise the money to pay for this met with only partial success – perhaps people had little enthusiasm for the idea of a brick tower in the middle of town. Due to the lack of funds the subscription lists were left open for a further twelve months. By this time about £140 had been raised – thankfully not enough for the projected brick turret and clock but enough for a new movement and dials to be fitted into the old tower. A seven day movement was ordered which needed a taller tower so that the two heavy weights which powered the clock, had room to run the clock for a week before they had to be wound up to the top again. The local firm of John Beard won the contract to heighten the tower by about three feet and once this was completed the new movement and larger dials were installed toward the end of 1888 – a year after the Jubilee. The dials were illuminated by gas flares using an automatic apparatus to turn the gas on and off at night according to the day length through the year and from early morning until daylight to serve those people going to work.

The clock was made and installed by J Smith and Sons at the Midland Steam Clock Works, Derby. This firm still exists and supplies turret clocks and indeed still gives the Coggeshall clock it’s annual service and check-up. Smiths also supplied the two 3’6″ cast-iron frames for the dials, made at Browns Foundry Derby, which were fitted with opal glass.

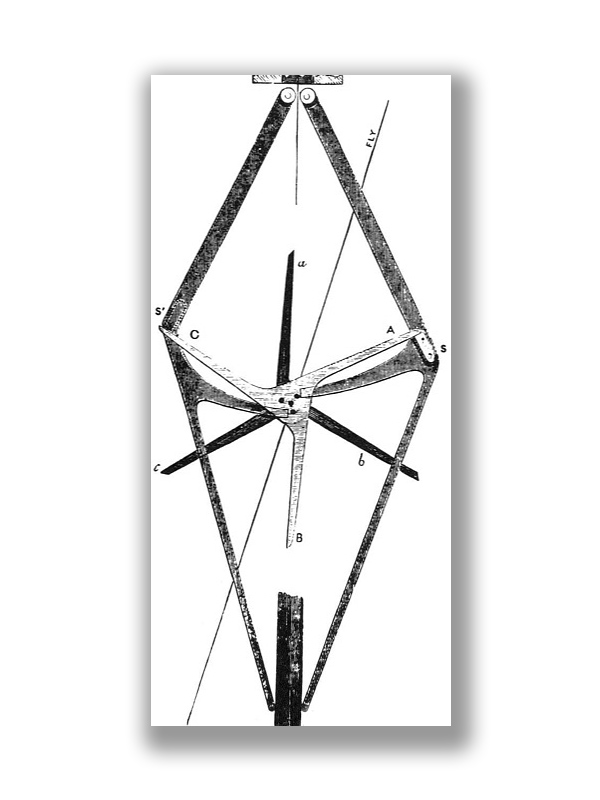

The clock has a double three-legged gravity escapement designed by E. B. Dennison (later Lord Grimthorpe) for the clock of ‘Big Ben’ 1854-9. This movement represents Victorian imagination and engineering at its finest. The clock makers were recommended by Lord Grimthorpe himself who said ‘Go to Smiths of Derby, they will clock you as near to eternity as possible’.

The clock is powered by two large weights which have been wound up weekly since the clock was started – 46 turns for the striking mechanism and 54 for the ‘going’ side – something like half a million turns since 1888. Not counting leap years the clocked has ‘ticked’ around 21 billion times and remains as accurate a time-keeper as ever. There has been one concession to progress over the past century, as the faces are now illuminated by electricity.

You can see an animation of the escapement working here

Html Light Grey background ignore this text it is just to increase the picture size

ignore this text it is just to increase the picture size

ignore this text it is just to increase the picture size

The Grand Opening

At 6 pm on Monday December 17th, 1888, Mr. Osgood Hanbury, the young Squire of Holfield Grange, cut a string which set the newly installed Jubilee Clock going.

The day had started with the firing of cannon, followed by the ringing of the Church bells at 7 am ‘the Coggeshall ringers ringing the date touch of Bob Major in a creditable manner’. [The ‘date touch’ is one change for each year.] After the 1888 changes which took one hour and fourteen minutes, the ringers adjourned to the Woolpack Inn where they were regaled with a good dinner and refreshments.

The town was gaily decorated with flags and streamers, the shops being closed at 5 o’clock to enable both tradesmen and assistants to take part in the rejoicings. Several shops were illuminated with Chinese lanterns and a bandstand was erected on the Market Hill to accommodate the Church Brass Band, under it’s Conductor – Mr W Tansley. After the clock had struck six the National Anthem was played, followed by the playing of popular airs until nearly 7 pm when the musicians adjourned to the National Schoolroom to lead the torchlight procession in which over 300 people took part dressed in fantastic costumes – one of those taking part being Mr Dick Nunn, the blacksmith, who was covered with small horse-shoes. The procession passed through the Vicarage Grounds for the benefit of the Vicar’s invalid son, Master Bernard Patch, before returning to the Market Hill for fireworks. These included the home-made serpents for which Coggeshall was noted [now called jumping jacks] – the ladies taking refuge at windows! Unfortunately fog came down which spoiled the effect of rockets although a huge bonfire helped to dispel the gloom, everyone going home we are told soon after 11 o’clock.

The bell which strikes the hours sits in a cupola above the tower and was in position well before the 1888 refurbishment. It was cast by the Whitechapel Bell Foundry in London and according to their records it was invoiced to Mr Knight of Coggeshall on 19th January 1843 and cost £20 5s 4d. This may have been John Knight who was a Watchmaker and lived in Church Street and may perhaps have had responsibility for the town clock at that time.

The bell is almost 24 inches wide and 20 inches high and weighs around 3 hundredweight. (60cm x 45cms and 152 kg)

The inscription cast around the top reads;

‘ THOMAS MEARS FOUNDER LONDON 1843’

Mears was born in 1781 and in 1810 was the master bell founder at the Whitechapel Foundry. He took over the factory in 1828 and when he died his two sons took charge.

Over the years the clock tower has been painted various colours – cream, slate grey and the distinctive dark blue which it bears today. It is not clear what its original 1888 colour was – black and white photographs show it as a mid grey tone. However when it received it first repaint it was to be in a ‘good stone colour relieved by stencil designs as before’. Exactly what they thought ‘stone colour’ was, is not obvious now.

It has always been sensitive to snow which collects in the lower part of the bezel and stops the minute hand from moving – but this does not stop the clock itself so the minute hand resumes moving when the snow melts – showing the wrong time of course!

The hurricane of 1987 displaced the boss and wrought iron weather-vane, all of which looked to be in danger of tumbling to the ground. The whole unit was removed by the fire brigade rather theatrically the next night in front of a considerable crowd. After repairs and re-gilding the brigade put it back as well.

It is difficult to imagine Coggeshall without it’s clock which has been there overlooking so many events; Coggeshall Carnivals, the gathering of waggons for the Sunday School outings, the muster of the Territorial Army, of the Essex Hunt, meetings such as the one where Joseph Arch of the Agricultural Labourers Union addressed a huge crowd, the recruiting meetings on Market Hill in World War I and the soldiers who came to Coggeshall, many never to return. Then World War II when warplanes friendly and otherwise flew overhead and the siren on the fire station just opposite blasted out its warnings and airmen from the USA arrived and later the joyful celebrations of VE Day – there have been four coronations and many street parties like the one held in 1988 to celebrate the centenary of the clock itself and another for the Jubilee of our own queen (the clock decorated for that party is shown on the left). Our clock remains central to the life of our town and long may it continue to do so.