COGGESHALL ABBEY

The convent of Coggeshall’s new abbey first assembled on the banks of the Blackwater on 3rd August 1140 when the monumental task of building an abbey got underway. These first monks, just twelve in total, were from the Savigniac Order and had come from the mother house in France. Some 27 years later and then under the Cistercian order, the church was complete and on 15th August 1167 the bishop of London dedicated the high altar to St. Mary and St. John the Baptist.

The land for the abbey and the substantial estate to support it, amounting eventually to some 50,000 acres, had been given by the wife of King Stephen, Queen Matilda of Boulogne.

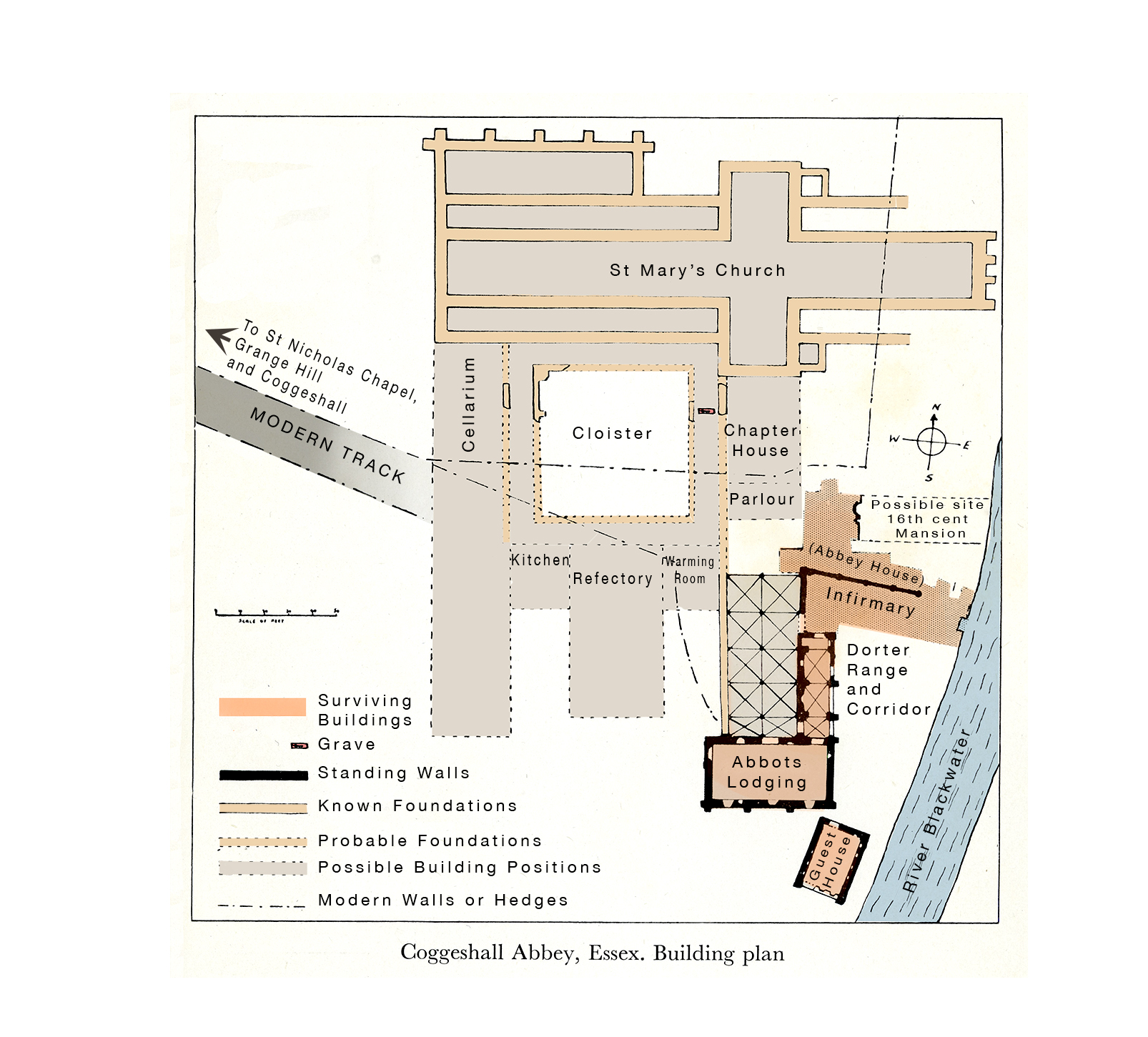

The abbey complex was built in a quiet spot by the river exactly as was required by the order. The church was large and it’s interior would have been very austere and unpretentious. As well as the church there was a Cloister enclosed by various buildings including the Chapter House, Refectory, Library, Dormitory or Dortor and Infirmary. Adjoining them were the Frater House or Great Parlour, the Abbot’s Lodgings and the Hospitium or Guest House.

The plan shown here is by John Gardner based on his research and excavations in the 1950s & 1960s.

A model of Coggeshall Abbey by Ian Stock derived from John Gardner’s plans.

The model is on exhibition on the museum.

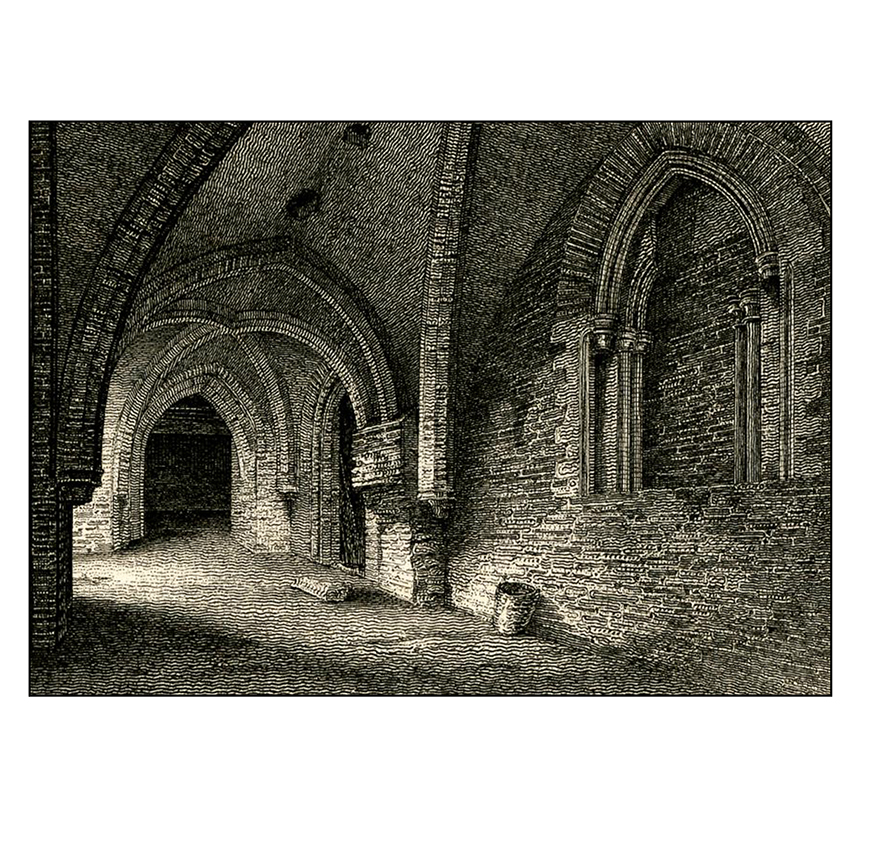

The building was of rubble, mostly flint, embedded in mortar but importantly, bricks were used extensively. Very sophisticated moulded bricks, were designed and made for the shaped mouldings around the windows, doorways and vaulting. There was some stone but this being expensive was used sparingly for capitals, corbels and column bases.

The technology of brick-making had been lost since roman times and these Coggeshall bricks are among the earliest made in England since then. Craftsmen from other monastic building projects in continental Europe were probably brought to Coggeshall by the monks to set up the brick-works. These were nearby where good quality clay was found at Tilkey – named after the tile-kilns sited there. The tiles were much larger than modern bricks up to 24 inches – 60 cms across and 2 inches – 5 cms thick. The word tile can be confusing but the modern word ‘brick’ did not appear in English until some 300 years later.

The walls of the abbey were plastered and painted with red lines to resemble the divisions in stonework.

The engraving shows the moulded brickwork used in the windows, around the doorways and for the vaulting.

This is the corridor below the Dorter as it appeared in 1816.

Html Light Grey background ignore this text it is just to increase the picture size

ignore this text it is just to increase the picture size

ignore this text it is just to increase the picture size

Building work did not stop in 1167; the abbey continued to be extended and developed and within a hundred years a Gatehouse Chapel and the huge barn now called the Grange Barn had been built.

Coggeshall historian John Gardner wrote; The rules in the early days of the monastery were strict. Meat and even fish were forbidden to all except the sick and the daily meal consisted of a pound of bread and two dishes of vegetables ‘cooked without the use of grease’.

The monks slept in their habits on straw, and the washing of clothes was not allowed although they could be shaken and hung in the sun. Cleanliness was thought to be ungodly, in 1202 a Spanish abbot was deposed for using baths and as late as 1437 it was decreed that any monk who took a bath once a month should be put on bread and water until he saw the error of his ways.

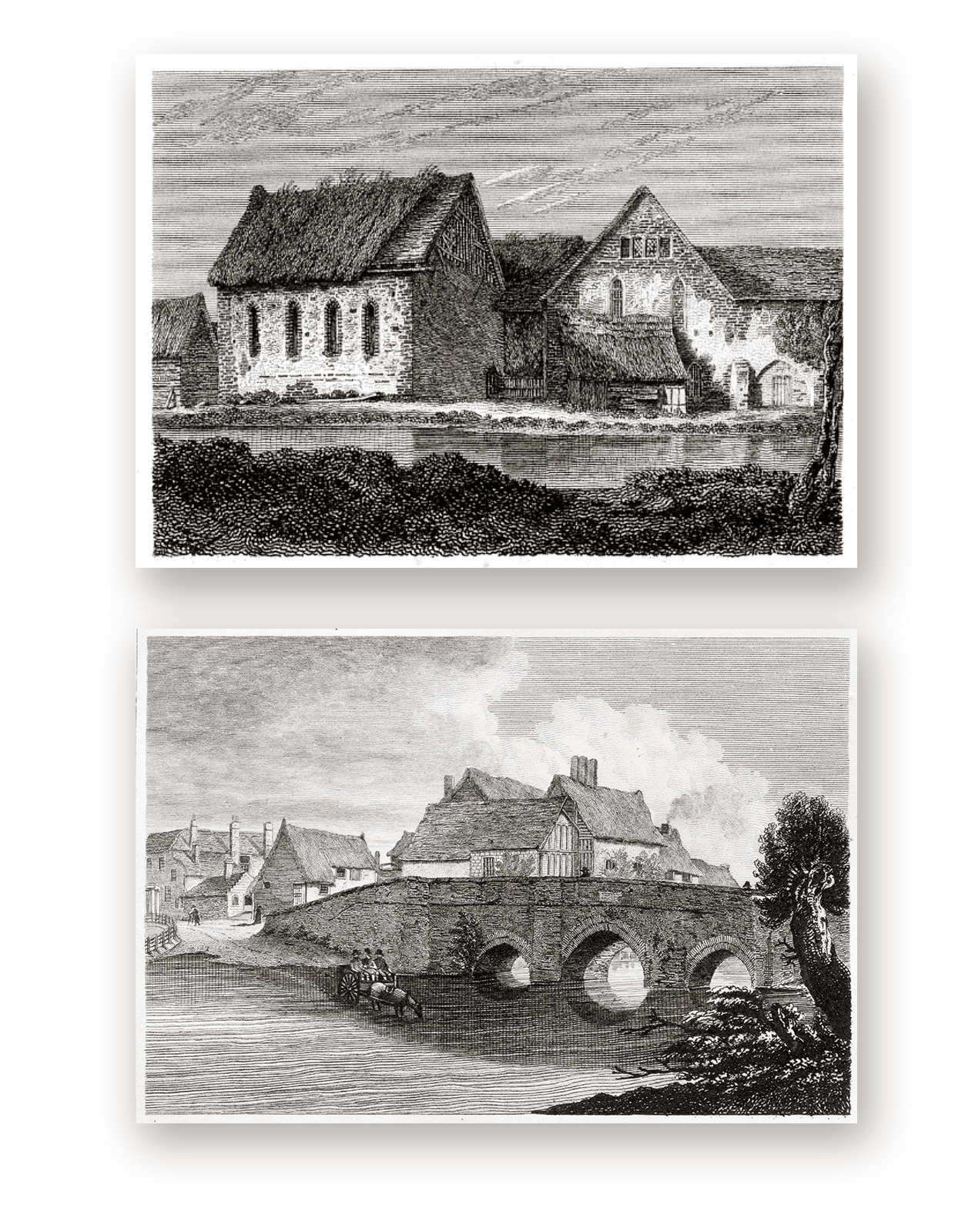

To provide a better flow of water to their watermill, a new channel was dug to the south of the original course of the river and a three-arched brick bridge built across it – now known as Stephen’s Bridge or the Long Bridge. It was here on the town side of the bridge that a Rood or Cross was put up marking the entrance to the outer precinct of the abbey. On the other side of the river was the abbey brewery parts of which still remain at the centre of the present house on the site, ‘Monkwell’.

The abbey ruins seen across the River Blackwater shown in an etching of 1816.

From ‘The Antiquarian Itinerary’.

Stephen’s Bridge, spanning the new course of the river from an engraving of 1819.

From ‘Excursions through Essex’.

Ralph of Coggeshall as he came to be known was the sixth and most eminent abbot. He was already a celebrated member of the order before he came to Coggeshall due to his exploits in the Holy Land. He was present at the fall of Jerusalem and it was there during the siege that he suffered a head wound which caused him much suffering in later life. When he returned to England he retired to monastic life at Coggeshall abbey and set to work on the Chronicon Anglicanum which has brought him lasting importance.

The grave marked on the abbey plan above might be his – you can read more about him here.

Little is known about the day to day events of Coggeshall Abbey, Ralph tells us that in 1216, while tierce was being said, some of King John’s army violently entered the abbey and carried off twenty-two horses belonging to the bishop of London and others. The horses were were apparently in the nave of the church as the stables were too small. The other story recounted by Ralph is of a rather a mysterious and ghostly event that happened in the time of Peter, the fourth abbot from 1166 – 94. A lay brother called Robert who had the care of the guests, entered the guest hall as usual before the hour of refection and there found several persons dressed as Templars. He conversed with them and reported their arrival to the abbot, but on his return found no one, and the porters said that no such persons had passed the gates.

During the Peasants Revolt of 1381 the abbey was attacked and goods and charters, writings and other muniments, were carried away and destroyed.

An old photo taken in about 1900 shows the Guest House in use as a barn.

There was a settlement at Coggeshall and a priest well before the monks arrived. This was probably in the area of upper Church Street. The church itself was beyond the control of the abbey, enjoying rights also granted by Matilda and there was always a tension between abbey and church. The vicar of Coggeshall was locked up in Colchester Castle for stealing fish from the abbey stews. Following an adjudication in 1223 – 24 which the abbey lost to the church, the abbot converted his Gatehouse Chapel into a parish church in the newly invented ‘Little Coggeshall’ to claw back a little from the established church over the river in Coggeshall.

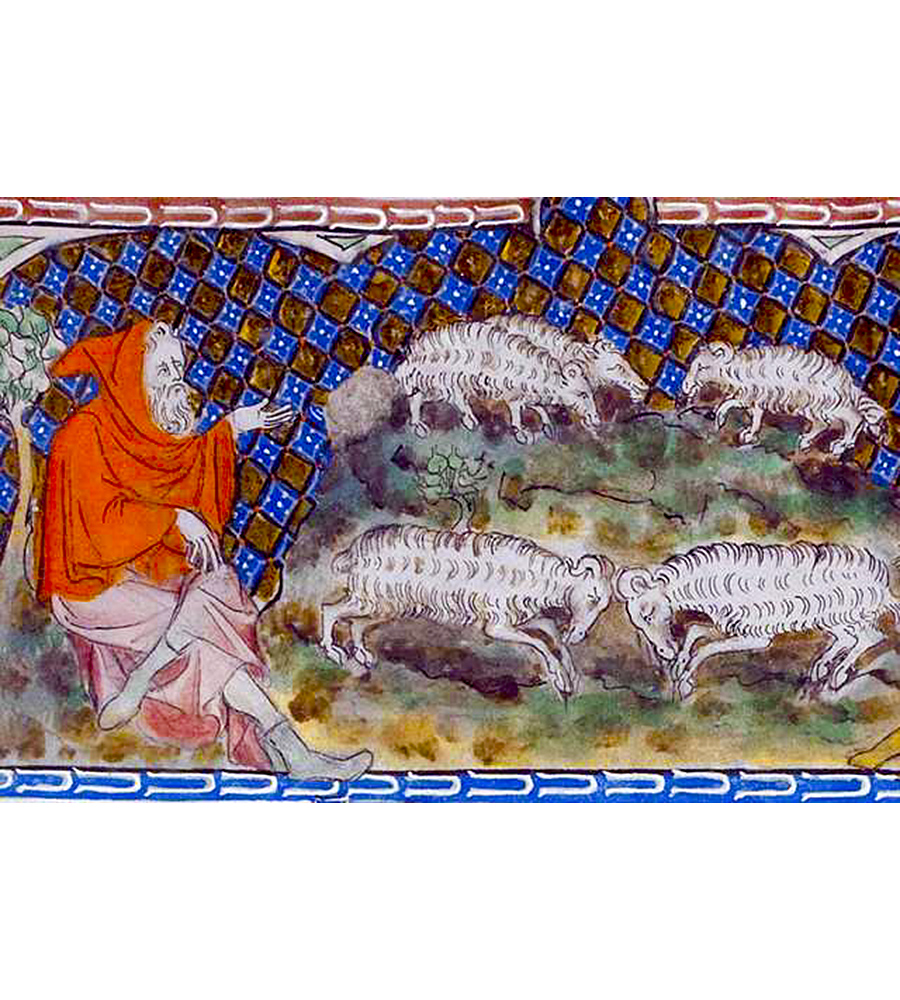

The abbey prospered on profits derived from the wool trade – a speciality of the Cistercian order. Although the local wool was of poor quality compared to that from Gloucestershire it did carry a premium, the result of good husbandry and especially in the cleaning, sorting and grading of the wool. The abbey also enjoyed exemption from tolls which significantly reduced the cost of transport. It is known that as early as 1280 Coggeshall wool was being traded in the Low Countries and by 1315 in the markets of Florence. The abbey became very prosperous with 24 monks and 40 lay brothers at its peak.

The abbey sheep did best on the open higher land – the ‘downs’ and the names of two of these Coggeshall downs are known – Ingory Downs and Monks Downs. It was probably with the idea of selling wool that Coggeshall was granted it’s weekly market in 1256. This brought an increasing wealth to the town and in the thirteenth century the centre of the settlement moved from around the church to surround the market on what is now called Market Hill. The prosperity of the new town also grew with the developing industry of weaving wool into cloth – a trade for which Coggeshall was to become very famous and enormously wealthy.

Over time there was a relaxing of the rules of the Cistercian order including that forbidding monks from having personal possessions. The economic health of the abbey declined for a variety of reasons and many of the smaller monasteries were suppressed by the church itself and the money raised used to support schools. In 1518 a private individual, Sir John Sharpe, had a lease with the Abbey for his mansion house within the precinct itself.

The campaign of Henry VIII to dissolve the monasteries caught up with Coggeshall Abbey on the 5th February 1538 when Abbot More handed over his house to the crown, reputedly in financial ruin. The church was quickly demolished – Cromwell it is said used Italian labour and explosives to get the job done quickly as a deterrent to any monks returning to re-establish themselves.

Luckily at the time of the dissolution the lease on what had been Sir John Sharpe’s mansion within the abbey was held by Clement Harleston and this is what saved the buildings that stand today. This old mansion stood for a further hundred years before it was demolished in about 1639 when the present east wing was built by Richard Benyon, husband of Anne Paycocke, who had inherited the abbey remains.

List of the Abbots of Coggeshall Abbey

In the Museum there is a display of Coggeshall bricks and different types of medieval tiles.

There is also more information about Coggeshall abbey with pictures and the works of G. F. Beaumont and J. S. Gardner (both eminent Coggeshall historians) about Coggeshall Abbey and it’s bricks which are available for study.